Polymyositis is an inflammatory myopathy. It is believed to result from an autoimmune reaction, whereby the body's own immune system attacks the muscle cells. This results in the breakdown of muscle. The result of this attack on the muscles is inflammation, with muscle tenderness as an occasional complaint. The onset of symptoms may be acute, but the condition usually progresses slowly. If left untreated, the patient's ability to ambulate may be compromised. Once the diagnosis is established, treatment is straight forward and often successful in reversing the symptoms.

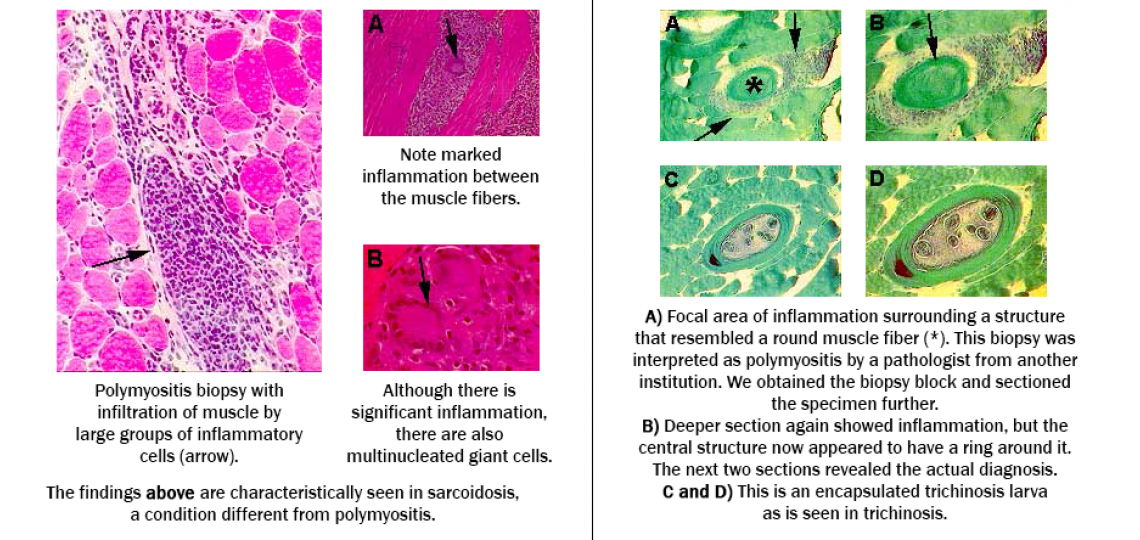

The first step in the diagnosis of polymyositis is obtaining a history and physical examination compatible with the picture usually seen in this entity. The clinician will then obtain blood to check for creatinine phosphokinase (CPK) level, which is usually elevated. An electromyogram is then performed which usually shows findings of muscle irritability in association with characteristic myopathic units. The next step in the diagnosis is the performance of a muscle biopsy. A muscle biopsy is necessary to differentiate between polymyositis and other inflammatory myopathies and to also rule out any other muscle condition that could be mimicking polymyositis. When the diagnosis of polymyositis is confirmed, treatment can be initiated.

Polymyositis is thought to be an autoimmune disorder and its effective treatment consists of immunosuppressive and immunomodulating agents. The most widely used and most effective first-line agent is prednisone. Prednisone may be started at high doses orally every day, and maintained at that level for three to four weeks until a favorable response is observed. A favorable response usually consists of improvement of the symptoms and a decrease in the CPK level. Prednisone is then slowly tapered to reach an every other day regimen. Every other day regimen has been proven to cause less side effects. Tapering of prednisone is slowly continued until the minimum dosage at which symptoms are controlled is reached. In a few cases (about 10 percent) patients go into remission and remain symptom-free without immunosuppression. If steroids are ineffective or cannot be tolerated, other immunosuppressants have also been used with good results.