The Agent

Zika virus, first identified in 1947 in Uganda, had been thought to produce a rare and mild disease until it suddenly emerged in Brazil in 2015 and spread explosively through South America, Central America, and the Caribbean. The virus arrived in the United States in the summer of 2016.

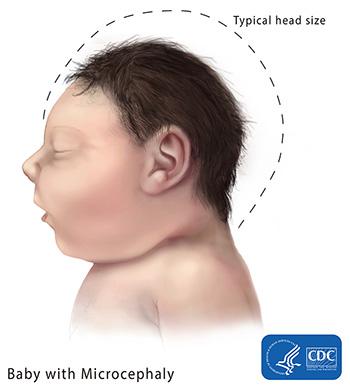

Zika virus is transmitted primarily by mosquitoes that thrive in tropical climates and urban areas. The virus can cause Zika virus disease. In most cases Zika virus disease is a mild illness, but Zika virus can cause a serious birth defect known as microcephaly, in which babies have abnormally small heads and symptoms that range from mild developmental delays to a fatal condition. Zika virus can also cause a neurologic condition in adults known as Guillain-Barre syndrome that results in muscle weakness or even paralysis in the worst cases.

Classification

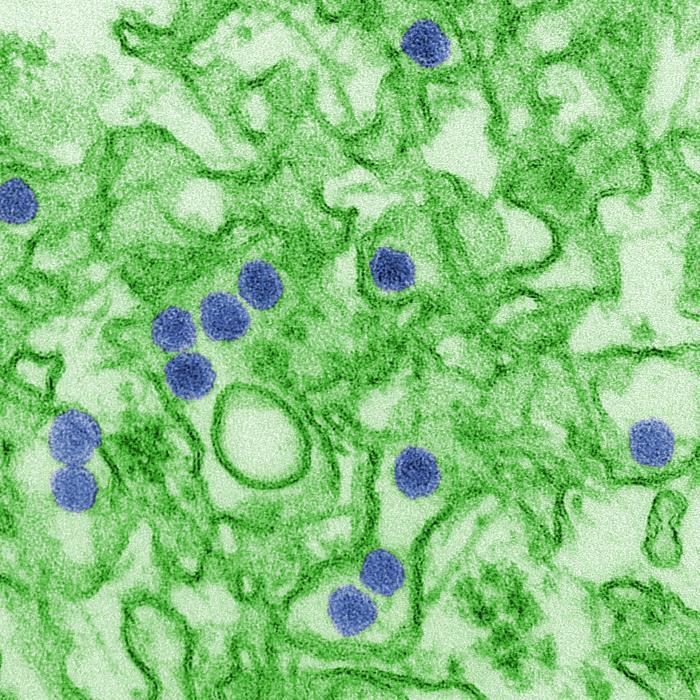

Zika virus is a member of a family of viruses known as Flaviviruses. This is the same family to which dengue virus, yellow fever virus, and West Nile virus belong. Flaviviruses are enveloped viruses that contain genomes which consist of nonsegmented single-stranded positive-sense RNA. The viruses are transmitted to humans by infected mosquitoes.

Zika virus and the other flaviviruses are part of a larger group of viruses termed arboviruses (for arthropod-borne). The defining characteristic of these viruses is that they are transmitted to humans via the bite of infected arthropods, most commonly mosquitoes and ticks. They are maintained in nature through a complex cycle in which they rotate between a vertebrate animal host and a blood-feeding vector that carries the virus from one host to another. Another recently emergent arbovirus is chikungunya virus, which belongs to the Alphavirus family.

Transmission

Zika virus is transmitted primarily through the bite of an infected female mosquito. Mosquitoes become infected when they bite a person who is infected with the virus. The virus then replicates and spreads within the mosquito so that when the infected mosquito bites again, the virus is spread to another person.

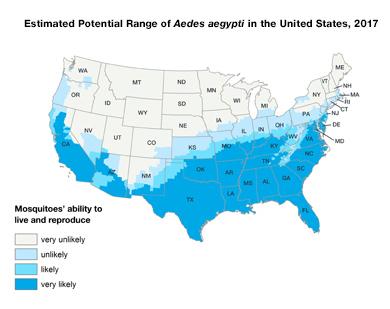

Two types of Aedes mosquitoes are capable of transmitting Zika virus – Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. These are the same species that spread dengue and chikungunya viruses. Aedes aegypti, which is found in tropical and subtropical regions, is the primary transmitter of Zika virus. Initially thought to be present only in 12 states in southern coastal areas of the United States, Aedes aegypti has now been found in about 30 states.

Although less common, there exist other routes by which Zika virus can spread. Zika can be transmitted from a woman to her fetus during pregnancy and through sexual contact. It is also likely that Zika virus can spread through the transfusion of blood and blood products.

Symptoms and Complications

Credit

Credit

Most people who become infected with Zika virus do not experience any symptoms. Those that do will usually experience only mild symptoms including fever, rash, headache, muscle and joint pain, and conjunctivitis. The symptoms generally begin about three to fourteen days after a bite from an infected mosquito and last for about two to seven days. Because symptoms may be nonexistent or similar to other viruses (such as dengue virus), many people might never realize they have been infected with Zika virus.

Zika virus disease is usually diagnosed based on symptoms, prior mosquito bites, and travel history. In some cases, infection is confirmed through laboratory testing using a polymerase chain reaction-based test and isolation of the virus from blood samples. Once infected, a person is likely to be protected from future infections by Zika virus.

In pregnant women, however, there is a much graver risk of complications from Zika virus infection. In 2015 in Brazil, an explosive epidemic of a condition known as microcephaly was correlated with the outbreak of Zika virus. Microcephaly is an uncommon disorder in which a baby’s head is much smaller than normal due to abnormal brain development while in the womb or shortly after birth. Babies with this condition will often experience developmental delays later in life and some may have vision defects including blindness. The problems affecting babies with microcephaly can range from mild to severe and can sometimes be life-threatening.

Microcephaly can be caused by a number of genetic and environmental factors, including Down syndrome and fetal exposure to a variety of toxins. However, the number of microcephaly cases during the Zika virus outbreak in Brazil was about twenty times higher than normally would be expected. Such a congenital malformation has not been seen with any other flavivirus or other arthropod-borne virus.

Although experts were initially cautious about ascribing the cause of microcephaly to Zika virus, the link was strengthened by studies that detected the presence of Zika virus in the amniotic fluid and brains of microcephalic babies. Laboratory studies have further shown that Zika virus can infect and kill human fetal brain cells growing in cell culture and also in mice. By April 2016, the body of accumulated evidence was strong enough to arrive at a scientific consensus that Zika virus causes microcephaly.

In addition to microcephaly and other congenital abnormalities in the developing fetus and newborn, Zika infection during pregnancy can result in fetal loss, stillbirth, and preterm birth.

Another complication of Zika virus is Guillain-Barre syndrome, a rare condition in which the body’s immune system attacks part of the nervous system. This syndrome also can be caused by a number of other viruses. Symptoms include muscular weakness and tingling in the arms and legs. In the most severe cases, a person may be almost completely paralyzed and the respiratory muscles affected, and the patient will require hospitalization. Most people recover, but some may continue to experience some degree of weakness.

Outbreaks

Zika virus was first isolated in 1947 in the Zika Forest of Uganda (Zika means "overgrown" in the local language) from a rhesus monkey during a survey to detect yellow fever infections in primates. It was subsequently identified in humans in 1952 in Uganda and Tanzania. Over the next couple of decades, there was evidence of human infections in other African countries, including an outbreak in Nigeria in 1973; human infections were also reported in countries in Asia.

The first known large outbreak of Zika virus occurred on remote Yap Island in the Pacific Ocean in 2007, with an estimated number of 5,000 cases of mild disease. This was followed in 2013-2014 with an outbreak in French Polynesia, with an estimated number of 20,000 cases. It was during this outbreak that an unusual increase in the number of Guillain-Barre syndrome cases was first noted.

However it was not until March 2015, when an outbreak erupted in Brazil, that Zika virus became a worldwide concern. The illness spread rapidly to countries in South America, Central America, the Caribbean, Africa, and other regions. For the first time, Zika virus was associated with the serious complication of microcephaly and other fetal malformations.

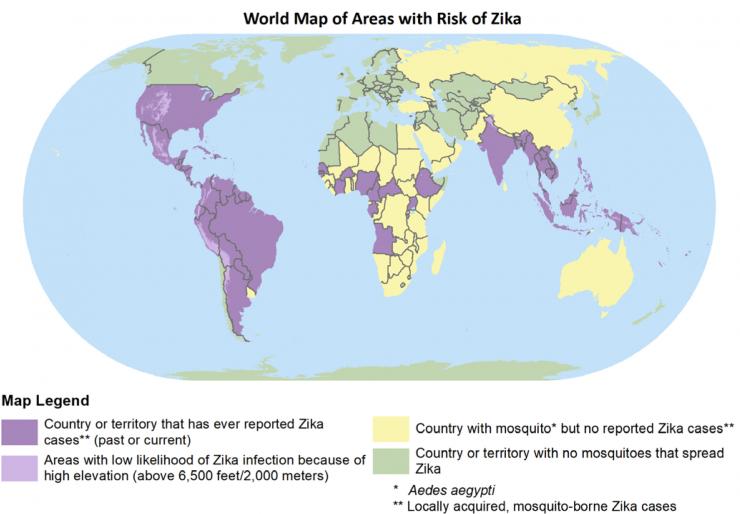

As a result, in 2016, the WHO declared a public health emergency and U. S. health officials issued an unprecedented travel warning advising pregnant women to avoid travel to countries where the Zika virus was circulating.

Altogether, more than 85 countries and territories have reported evidence of mosquito-acquired Zika infection. Microcephaly and other central nervous system malformations thought to be associated with Zika virus infection have been reported in at least 30 countries, and an increased incidence of Guillain-Barre syndrome has been reported in more than 20 countries. Brazil has suffered the greatest impact from the virus. It has been estimated that more than 200,000 cases of Zika virus disease occurred, and approximately 8600 babies were born with malformations in that country.

The epidemic has since waned and as of May 2019 no countries were reporting active outbreaks of Zika virus. However, Zika virus - and the mosquitoes that transmit it - have not been eliminated and a low risk of currently undetected transmission remains. Therefore caution is still advised especially for women (and their partners) who are pregnant or considering pregnancy.

Zika Virus in the United States

The first cases of Zika virus disease were reported in the United States in 2015. All 62 cases resulted from travel to areas where Zika virus was circulating within the local mosquito populations. The total number of travel-associated cases in the United States rose sharply in 2016 to nearly 4,900, and as of June 2019 stands at approximately 5,700.

Cases of Zika virus infection by mosquitoes within the United States, that did not involve travel, first came to light in July 2016. The initial cases were detected in the Miami area. Shortly thereafter, local transmission was also reported in Texas.

By the end of 2016, there were 224 laboratory confirmed cases acquired through local mosquito transmission according to the CDC. With the exception of six cases in Texas, all of the remaining cases occurred in Florida. In addition, 45 cases were acquired through sexual transmission.

In 2017, there were two cases in Florida and five in Texas that were acquired locally, but no locally-acquired cases have been reported in the United States since then (as of May 2019). However, low numbers of infections continue to occur in travelers returning from affected areas.

As of June 2019, there have been 231 symptomatic cases acquired through presumed local mosquito-borne transmission of the virus, and 52 cases acquired through sexual transmission since the outbreak began. More than 2,300 pregnant women in the United States have had laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection, with 116 reports of live-born infants with Zika-associated birth defects and nine pregnancy losses with Zika-associated birth defects. The birth defects include microcephaly and other abnormalities of the brain, as well as abnormal eye development and hearing loss.

Local transmission of Zika virus began in the U.S. territories of Puerto Rico, American Samoa, and the U.S. Virgin Islands in 2015. Puerto Rico has been the most severely impacted with a total of over 37,000 infections, almost all of them acquired locally. There have been over 4,800 pregnant women presenting with laboratory evidence of infection, with 167 reports of live-born infants with Zika-associated birth defects and eight pregnancy losses with Zika-associated birth defects. As of June 2019, local transmission is still ongoing, but the number of new cases is much lower than the peak year of 2016.

The Problem

Treatment and Prevention

There is currently no cure for Zika virus disease and no drugs to treat it. Scientists have begun the process of developing a vaccine, but it is expected to take years to develop one that would be widely available.

For now, mosquito control is considered the best way to prevent infection and combat Zika virus. This includes personal protection measures when outdoors such as minimizing exposed skin and using mosquito repellents that contain DEET and by eliminating places in which the Aedes mosquitoes can breed such as outdoor containers that collect pools of stagnant water. However, this can be a challenging undertaking especially in densely populated areas and less developed countries, and people living in places without window screens and air conditioning are at higher risk. In addition, safe sex practices are recommended to prevent sexual transmission of Zika virus.

Spread of Zika Virus

Zika virus emerged in the Americas, without warning, and spread rapidly. Widespread infection by Zika virus was worrisome because the virus had not previously existed in the Americas, and therefore virtually no one was immune to the virus; there existed the potential for millions of people to become infected. As with other mosquito-borne diseases, however, the outbreak in the United States and Europe was less extensive than in the developing countries afflicted by Zika virus, at least in part due to better surveillance, mosquito control, and healthcare infrastructure.

To date, cases have been reported in over 86 countries and territories, and it is expected that Zika virus will continue to expand its range into additional regions where the Aedes mosquitoes are found, including areas of the United States. The mosquitoes that transmit Zika virus are present in about 30 states during the warmer months, so much of the United States is potentially at risk with Florida and Texas considered among the highest risk states especially in poor, urban neighborhoods.

The spread of Zika virus, as well as other emerging Aedes mosquito-transmitted diseases, such as dengue and chikungunya, is due in part to man-made factors. Urbanization and climate change create additional environments for the Aedes mosquitoes to live and breed.

Human migration facilitates the spread of viruses around the globe. Air travelers can easily spread viruses when they become infected in one country and then board a plane to travel to another country and pass on the virus. Because the majority of Zika virus-infected people do not have any symptoms, it is not possible to detect infected people entering a country.

The Research

Although Zika virus was discovered in 1947, there has been little research conducted on the virus because until recently it was considered an obscure virus that caused only sporadic and relatively mild illness in Africa and Southern Asia. With the jump into the Americas, the large increase in the number of human cases, and the link to more severe illness, research into Zika virus has taken on a much greater importance and urgency.

There are several research projects related to Zika virus ongoing within the Department. Dr. Rebecca Rico-Hesse and her colleagues are involved in a number of experiments to isolate and analyze Zika virus samples to learn more about the virus and how it replicates and to determine the potential for transmission of Zika virus in mosquitoes collected in the Houston area. Dr. Shital Patel and coworkers are investigating immune responses in patients infected with Zika virus to inform future vaccine clinical trials. Additionally, studies are being conducted to optimize detection of Zika virus in body fluids.

The long-term goals of research on Zika virus include learning more about the transmission pathways of the virus, understanding how the virus causes disease, and discovering its effects on the human immune system. Furthermore, researchers would like to develop a safe and effective vaccine against Zika virus and develop more accurate tests to detect the virus in infected people.

Investigation of Host Cell Types and Entry Factors that Mediate Zika Virus Transmission

In one study, Drs. Rico-Hesse, Jason Kimata, and their colleagues investigated the host cell types and entry factors that aid in mediating the sexual transmission of Zika virus. They infected two types of human prostate cells - stromal cells and epithelial cells - with three isolates of Zika virus that were obtained from persons infected in the Americas. Using a variety of techniques, they found that prostrate cells express several well-characterized factors used by flaviviruses to attach to cells, and that Zika virus, but not dengue virus, can infect and replicate in these cells.

The results indicated that Zika virus can infect prostate stromal mesenchymal stem cells, epithelial cells, and organoids made with a combination of these cells. They further found that Zika virus appears to favor infection of prostrate stromal cells over epithelial cells; this could possibly indicate a preference for infection of stem cells in general. Overall, the results of this study suggest Zika viral replication occurs in the human prostate, and can account for the secretion of Zika virus in semen, thus leading to sexual transmission.

Effect of Mosquito Saliva Alone on the Human Immune Response

In another line of research, Rico-Hesse and coworkers, using a 'humanized mouse' model to study dengue virus infection, found that mosquito saliva alone - in the absence of any virus - can trigger a human immune response which may significantly affect disease development not only by dengue virus, but also by other Aedes mosquito-transmitted viruses including Zika virus and chikungunya virus.

The researchers used a model system that consisted of mice naturally born without their own immune system, but which had received human stem cells which could then give rise to many of the components of the human immune system, so factors involved in disease development could be studied. These animals were injected with dengue virus either through a mosquito bite or through needle injection.

They found that animals receiving the virus through a mosquito bite developed a more human-like disease with more of a rash, more fever and other characteristics that mimic the disease presentation in humans than did the needle-injected mice.

This led the scientists to investigate the role of mosquito saliva on disease development, hypothesizing that the mosquitoes may not just be acting like ‘syringes,’ merely injecting viruses into the animals they feed on, but rather that their saliva may contribute significantly to disease development.

To test this idea, virus-free mosquitoes were allowed to feed on the humanized mice, and then the researchers took blood and a number of other tissue samples six hours, 24 hours and seven days after the mosquitoes bit the mice. They determined the levels of cytokines, as well as the number and activity of different types of immune cells, using highly sensitive techniques and compared these results with those obtained from humanized mice that had not been bitten by mosquitoes.

They discovered that mosquito-delivered saliva induced a varied and complex immune response. Both the immune cell responses and the cytokine levels were affected. At various time points, the levels and activities of other types of immune cells also increased as others decreased.

Overall, the researchers found evidence that mosquito saliva alone can trigger long-lasting immune responses – up to seven days post-bite – in multiple tissue types, including blood, skin and bone marrow. The diversity and complexity of the immune response was a surprise to the investigators.

The researchers would now like to determine which of the more than 100 proteins in mosquito saliva are mediating the effects on the immune system and whether these effects could increase disease development. Identifying these proteins could help in the design of strategies to fight transmission of Zika, dengue, and other viral diseases transmitted by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

Immune Responses in Patients Infected with Zika Virus

The Vaccine Treatment and Evaluation Unit at Baylor College of Medicine (in collaboration with other study sites, including Emory University School of Medicine), was awarded more than $1 million in funding from the National Institutes of Health to study people infected with Zika virus to better understand immune responses following infection.

The study aims to ascertain how the immune system responds to Zika virus infection and whether and how the immune response might differ from person to person, especially for those who have mild versus more severe symptoms or for those who have been previously infected with another flavivirus. This knowledge is necessary to aid the development and testing of an effective vaccine against Zika.

Dr. Shital Patel, principal investigator of the study, and coworkers began enrolling volunteers with Zika virus infection (and control subjects) in July 2016. Participants in this study provide blood, saliva, and urine samples over the course of several months. The researchers then conduct laboratory tests on these samples to determine (1) how the human body protects itself from the virus (by assessing antibody formation and the activation of certain types of immune system cells such as T cells) and (2) how long the virus lasts in certain parts of the body (by using PCR tests to detect viral genetic material in different body fluids).

Dr. Patel and her team have published a report, where they examined the responses of several types of immune cells and the levels of viral persistence in five patients with acute symptomatic Zika virus infection. They described the detection of Zika-virus specific antibodies and T cell activation, as well as viral RNA levels in body fluids.

In a subsequent study using samples obtained from patients with Zika virus infection, Dr. Hana El Sahly and colleagues found that Zika RNA detection was more frequent and prolonged in whole blood samples compared with specimens from other body fluids. They also detected differences in certain immune responses in patients who had previously been infected with dengue virus relative to those who had not had a prior dengue infection. Further, they identified Zika virus proteins most frequently targeted by T cells of the immune system.

Knowledge gained from this research regarding the types of immune responses to Zika virus infection and the length of viral persistence in an infected person will help inform diagnostic and infection control measures, as well as Zika vaccine development.

Detection of Zika Virus in Body Fluids

Diagnostic tests are currently available to detect Zika virus infection in infected patients. However, the tests have certain limitations. Detection of Zika virus RNA in a patient's blood serum or urine is limited to a timeframe of only one to two weeks following the onset of symptoms due to a rapid decline of the virus in these body fluids. A test for antibodies in patient serum is complicated by the fact that there is considerable cross-reactivity with other related flaviviruses. The detection of Zika virus is further challenged by the fact that about 80% of people with acute infection do not display symptoms.

It would be advantageous to be able to diagnose infection over a longer window of time, especially in high-risk patients such as pregnant women, or in those who develop serious complications such as Guillain-Barre syndrome.

With the goal of improving the ability to diagnose Zika virus infection, Drs. Shital Patel, Hana El Sahly, Kristy Murray and others have conducted a study to optimize detection of Zika virus. They evaluated and reported different viral RNA extraction methods to maximize the recovery of RNA from a number of body fluids to improve the sensitivity of Zika RNA detection tests.

Detection of Zika Virus in Body Fluids

Diagnostic tests are currently available to detect Zika virus infection in infected patients. However, the tests have certain limitations. Detection of Zika virus RNA in a patient's blood serum or urine is limited to a timeframe of only one to two weeks following the onset of symptoms due to a rapid decline of the virus in these body fluids. A test for antibodies in patient serum is complicated by the fact that there is considerable cross-reactivity with other related flaviviruses. The detection of Zika virus is further challenged by the fact that about 80% of people with acute infection do not display symptoms.

It would be advantageous to be able to diagnose infection over a longer window of time, especially in high-risk patients such as pregnant women, or in those who develop serious complications such as Guillain-Barre syndrome.

With the goal of improving the ability to diagnose Zika virus infection, Drs. Shital Patel, Hana El Sahly, Kristy Murray and others have conducted a study to optimize detection of Zika virus. They evaluated and reported different viral RNA extraction methods to maximize the recovery of RNA from a number of body fluids to improve the sensitivity of Zika RNA detection tests.

For More Information

- Information about Zika virus from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Information about Zika virus from the National Institutes of Health

- Information about Zika virus from the World Health Organization

- Information about Zika virus from the Pan American Health Organization

- Map displaying the worldwide geographic range of Zika virus

- Information about microcephaly

- Information about Guillain-Barre syndrome

Glossary

Learn more about some of the technical terms found on this page.